“The Chapter Houses pick up the slack by overworked sons or sons too distant to drive weekly, however those without sons must rely completely on the Chapter Houses for their firewood,” explained the local Navajo veteran, enjoying a savory Italian meal in Cortez.

He described his family’s process for providing wood for both his mother and his father-in-law, a former worker at the closed coal mine. His father-in-law has two daughters, one living in Phoenix and the other at their traditional homestead near the coal mine. Cattle and sheep are assets that need managing on their traditional land, and our veteran’s father-in-law is the only family member in his sh’aadaani (in-laws) with a pickup truck. With sisters and daughters, he stays busy.

Wood hauling has been significant for the Dine’, the people known as the Navajo tribe, for more than 700 years. It’s a pre-Columbian practice that continues to this day. The word ‘Anasazi’ is Navajo for ‘ancient enemy’ and evidence supports the Navajo / Dine’ use of lands at the foothills of Dibe’Ntsaa (Dibensa), the Dine’ name for the nearby mountain peak visible from Cortez known as Hesperus Mountain.

The timbers found in the New Mexico Chacoan site of Anasazi / Ancestral Puebloan culture were determined to be sourced over a thousand years ago from the nearby Chuska Mountains, now Navajo tribal land.

Within Colorado, the Mesa Verde civilization and Lowry Pueblo bracket Cortez to the south and north, but recent LIDAR sweeps show ancestral wickiup sites throughout Montezuma County and the Navajo Reservation to the west of town. Mesa Verde National Park is located just southeast of Cortez and has been established as Anasazi / Ancestral Puebloan, as is Lowry Pueblo.

A wikiup site is an oval, framed hut covered with brushwood or grass, and these structures were a preferred building method of the Navajo prior to their subjugation in 1868. There are disputes over the tribal history of these structures, but oral history has the lands used as both Ute and Navajo after the Anasazi.

Locals know this, outsiders (bilagáana / bilagaana in Dine’) don’t understand it. Cowboys call them ‘greenhorns’, Dine’ call them bilagaana. There are less conflicts between ‘Cowboys and Indians,’ both of whom have lived and worked side by side for centuries, than there are between Dine’ and well-meaning bilagaana, who don’t live with the land as the rural families have over decades.

Regardless, the location of the Colorado timber relative to the Navajo reservation means that firewood — a critical commodity on the reservation, especially during the brutal winter — must be trucked in.

Our veteran’s father-in-law staged several cords of aspen on his local son’s property and over the winter, he will be hauling it out to ‘the Rez’ – locals’ reference for the Navajo Nation – which will require multiple trips.

Firewood along the San Juan mountains near Cortez has become more complicated in recent years, due to the closing of the Black Mesa coal mine just south of Kayenta, Arizona. The coal mine distributed their coal byproduct at nominal costs throughout the tribal population for winter heating.

The closing of the coal mine has weakened the tribal electric grid, and increased energy burdens for the most vulnerable remote populations.

“Firewood is life for our people, and living traditionally has been made much harder without the coal.”

Local Navajo Veteran

Coal is denser in energy, easier to transport, and half the cost per million BTU when it was available from Black Mesa. It’s twice the cost now when it’s sold at Shiprock roadside in 50-pound bags.

Without the coal, firewood rules the winter, and the male relatives of each Nali’ – the native word for maternal grandmother – will spend their weekends picking up bedfuls of aspen from the waste products in Four Corners towns, such as Dolores and Mancos. In Navajo culture, Nali’, Cheii (grandfather) and the Masani’ (father’s parents) are the revered. The Nali’ is the matriarchal decision-maker, and each eldest daughter grows into that position.

The trips returning from Colorado’s mountains with wood are often over 100 to 120 miles each way, along winding and narrowing two-lane highways. US 491 and US 160 are dangerous with muddy switchbacks and troublesome weather and traveling them with a trailer loaded with 500-1000 pounds of seasoned wood required experienced, skillful drivers.

The Nali’ designates her oldest daughter to organize and supervise the heavy work that the sons and sons-in-law are expected traditionally to fulfill.

Those without family willing to do these trips are more vulnerable to winter conditions, which are often harsh across the Four Corners. For these most vulnerable, the Chapter Houses on the Rez are their main resource of fuel and other critical needs.

In May 2023, Tony Moore and Mary Lancaster, owners of Independent Logging Company (ILC), a forestry fuel mitigation and firefighting company, contacted the Navajo Chapter Houses with a proposal: Wood, using their unique operation with specialized equipment, delivered deeply within the Rez.

The firewood is byproduct for ILC – scrap from the heavy logs used in their log home manufacturing operation – but Tony and Mary know how valuable it is to the clans on the Rez. As a teen, Tony helped a local firewood business, watching Navajo pack their truck beds, car trunks, and even the laps of backseat riders with firewood in the 1980s.

Tony’s family settled the southwestern portion of Montezuma County outside what is now Cortez over 100 years ago. In the early Twentieth Century, Tony’s great-grandfather donated land for the community to use for the refuse dump. He and Mary expected to continue their generational contributions to the region after returning from Alamosa, Colorado in 2020 during COVID. Tony and Mary also run firefighting operations under ILC, which combined with the fuel mitigation operation, haul water trailers equivalent or greater in weight than twenty cords of wood.

Just as he had decided he’d own the 10-acre former movie theater lot, he decided he’d do something to pay it forward about the firewood situation when he came back to Cortez.

ILC is technically recognized as a ‘log home manufacturing yard’. Other building supplies for the region are brought from hundreds of miles away, often in Washington State, and ILC provides a local manufacturing center that reduces the cost of materials transportation and creates non-tourism jobs in Cortez.

Tony and Mary’s proposal was to dispose of the timber byproduct from the logging operation by delivering it directly to the 20 locations on the reservation, benefitting the area’s most vulnerable population with a much needed – and increasingly difficult to obtain – necessity.

This agreement between ILC and the Rez would solve a significant portion of the Four Corners region’s ‘double energy vulnerability’ which occurs when people are experiencing transportation poverty and energy poverty at the same time.

On the Rez, this condition is simply known as “Tuesday.”

There are nonprofit entities who deliver whole logs into the Rez, but time and effort to season, split, and distribute creates burdensome costs and additional risks. It’s safer, and more affordable, to employ local teenagers to haul the wood the last miles, deep into the Rez, and stack the wood. Opportunities to earn cash are few for these teens, and the last-mile hauling and stacking jobs at Chapter Houses provides local Dine’ teenagers a chance to make their way.

US 491 and US 160 are too dangerous for teenage drivers, loaded down with wood in trailers or pickup beds.

The deliveries directly to the Chapter Houses would reduce transportation risks, create much-needed jobs, reduce the tribal energy burden, and protect the vulnerable on the reservation.

Chapter Houses are the most local organizational structure within the Dine, providing the most resources for community development and support. They organize local events, provide cooperative resources such as tools or heavy equipment, and in this case, they are the point of negotiating bulk commodity deliveries.

Chapter Houses often combine resources for the smallest of the Dine’ communities, with the oldest or least economically suited at risk of being – literally – left out in the cold. Tony and Mary’s proposal addressed all these local challenges, even reducing ILC waste through reuse.

Everybody wins.

“The firewood delivery ILC was intending creates jobs for the younger teens on the Rez because they deliver it to our elders and handicapped people,” explained our Navajo veteran, who toured the ILC operation on Wednesday.

“It’s a seasonal occurrence that the Chapter Houses provide the cord wood to the elders because many Nali’ no longer have sons who traditionally would fell the trees, season them through the year, split and carry the wood to be stacked.”

When Tony and Mary brought their proposal forward during the veteran visit, they quickly learned that their neighborly gesture of goodwill actually addressed an urgent matter of life and death.

The Dine’ veteran’s assessment made clear that without split, seasoned firewood delivered to the Chapter Houses in bulk quantity, the most vulnerable of the Dine’ people will suffer this winter.

This common term “firewood” means significantly different things to an urban Durango or Denver resident than it does to the rurally raised Four Corners population of Colorado.

“City people just don’t understand the process of living with the land, where the land provides for most of your needs,” said Tony, who shared that his multigenerational ILC has been embroiled in land use and zoning issues for years. What makes instinctive sense to rural Four Corners residents is completely foreign to the urban Coloradan.

Firewood cannot simply be harvested and burned straight from the forests; it must age or become “seasoned.” ILC provides firewood like other local Colorado manufacturing operations with the added ability to distribute the wood to the Chapter Houses, benefiting the tribal communities.

Additionally, the ILC timber in question is derived from stewardship and fuels reduction efforts in the forests. Tony, a registered Cherokee tribal member, has had many trust relationships with other native firefighters for decades. Having grown up in Cortez, he has long understood what firewood means.

Emails from Mary to the Chapter Houses in May of this year offering the wood were unanimously met with enthusiasm. The native small business owner and the native Rez seemed to have found a mutually beneficial solution to a critical problem.

But City Planner Nancy had a different take, and the Cortez City Karens started throwing up barriers.

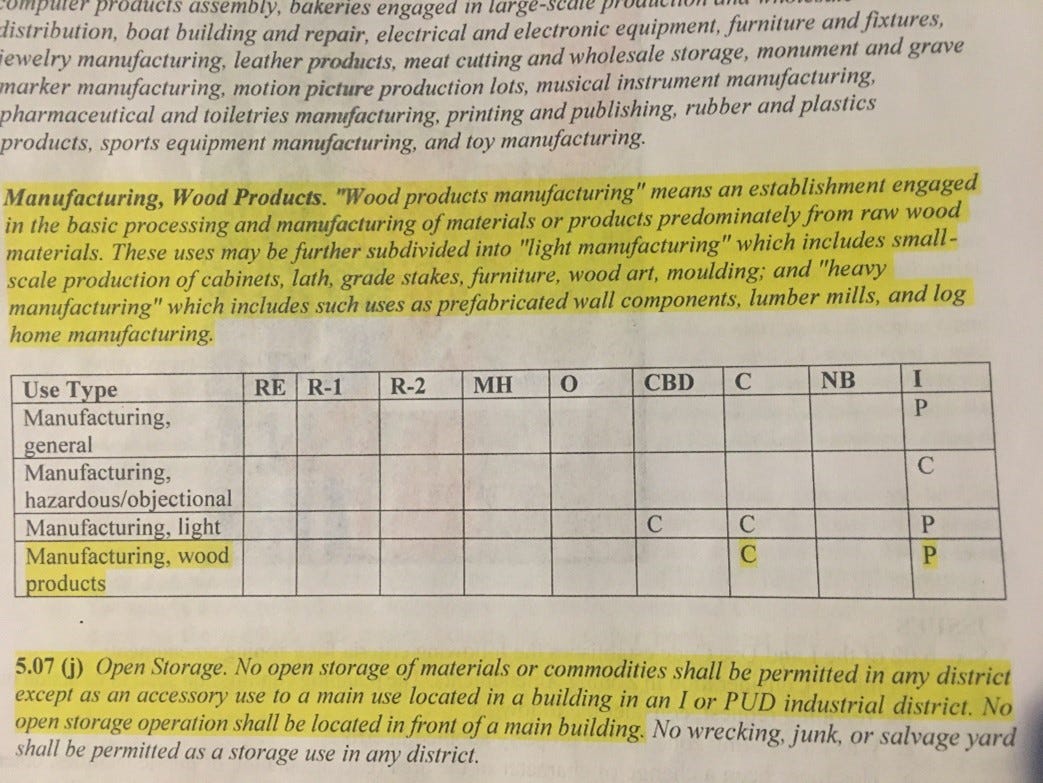

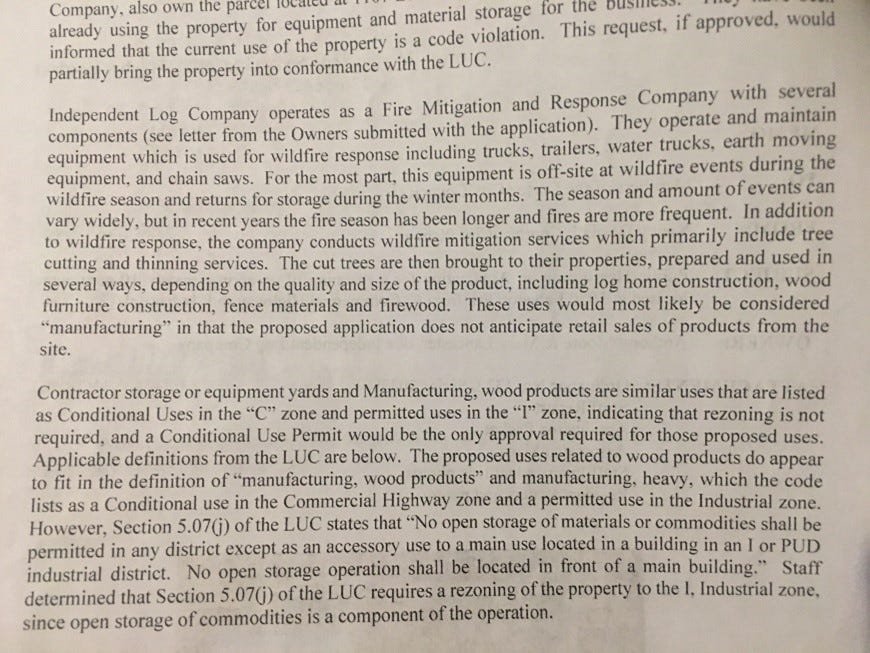

The City of Cortez had been previously involved with ILC concerning a commercially zoned lot just beneath the Cortez Industrial Park in the north part of the city. The plans for the operation included converting scrap into firewood. This component of the plan led City Contract Planner Nancy Dosdall to recommend a zone change to Industrial. This was due to the wording of ‘open storage of… commodity’ which she determined met firewood as it was presented to her.

Now, ILC usage of the 10-acres was subject to public comment and City Council decision on the zoning change to Industrial, rather than Commercial, zoning – placing burdensome requirements and additional costs on the business.

Firewood produced from ILC is a repurposing of the non-symmetric whole log ends produced in log home manufacturing. The firewood being “produced” and conversion from byproduct into commodity was solely presented by Nancy Dosdall, Cortez Planner, as unconforming to the Commercial zoning because firewood fits the City’s determination as a commodity in open storage under the land use code of Cortez.

The lot is directly adjacent to another other ILC owned property, grandfathered in as a sawmill. Tony and Mary can operate mostly unimpeded because of the historical use of one parcel being a sawmill, but the residents of the homes nearby feel that their claim is stronger to a noiseless environment.

Currently there is no code interpretation that says otherwise.

The commercial zoning “use by right” established everything for ILC except, it seems, commodities – which in this instance was interpreted by Nancy to mean the byproduct is immediately considered firewood. This appears to be either a mistake or corruption, and part two of this story will lay out the evidence for both to let the reader decide.

Still, Tony and Mary have bent over backwards in ceasing operations on a phone call basis to appease the city – to no avail.

There is little money in delivering the wood byproduct to the reservation, particularly after the lengthy inactive period and sunk costs brought on by the city’s delays as well as unfounded complaint-driven interruptions.

Tony and Mary were informed during the veterans’ tour Wednesday that, in their assessment, given its critical importance to the local indigenous people farther from Dibensa, the firewood hauling operation was a non-profit activity and a humanitarian one.

Research has shown that every degree of interior temperature decreasing beyond a certain range increases fatality rates in the elderly. This winter, if like last year, means dire consequences for delay according to physiological science.

The friendly neighborhood gesture by ILC owners, now being buried in bureaucratic red tape, is now known by the city staff to be a matter of life and death for the Nali’ of the affected Chapter Houses.

This matter’s importance was explicitly made known to them.

Three times.

According to public comment, the only objection the staff initially had to the agreement was the determination that the byproduct is a commodity, making the single question before the city: “At which point does byproduct turn into the commodity of ‘firewood’?”

In other words, it is the single change of delivering the byproduct to the Rez that led to the city rezoning the property. It’s a burdensome, bureaucratic paperwork change which could become deadly for some.

Natives also call that ‘Tuesday’. Welcome to life on the Rez.

Why are city staff taking such a risk with the area’s most vulnerable population? Well, it might just be good old-fashioned public corruption.

“We were told within the cycle that we could start operations, but we have had so many false complaints from citizens that starting up crews and laying people off would become a problem for our reputation,” explained Tony. “The local citizens group rallying around the trails neighboring our job site have created a situation where, until this zoning was resolved, the interruptions had my employees doing make-work tasks like planting shrubs and flowers.”

At least four members of a local activist group ‘Friends of Carpenter Trails’ have been protesting and calling in unfounded complaints against ILC since April 2023, resulting in lost worktime and delays of starting operations for the Chapter Houses.

The homes of ILC’s most vocal opponents were built on a landfill in the 1980s. There is slag remaining from that project, which has been incorrectly attributed to Tony and Mary. Both authors of this piece have reviewed the documents, one of which resulted in a Cortez Police investigation (call 23017731). The complaints against ILC were determined to be unfounded every single time, raising questions about the true motivations of the Friends of Carpenter Trails.

The core of the complaints seems to be city residents’ aversion to daytime noise or to conformal firefighting water tanks on the lot. They claim the water tanks — critical to local firefighting operations in fire-prone Colorado — to be “hazardous material.”

There is no hazardous material. They are water tanks. That is, these are just the unfounded allegations of angry City Karens with an unfounded 1980’s grudge. Part two of this story will lay out the connections of the decision-makers in the dispute and the audience can decide what’s really going on.

Every single false complaint cost Tony and Mary money as the labor costs associated with the repeated interruptions stacked up.

Independent Logging was losing revenue.

The expected Rez summer jobs for teens failed to materialize.

And the Dine’ Chapter Houses didn’t get their wood – for another year.

With the zoning dispute ongoing for years, we fast forward to September 26, 2023. To this point, local city planning and zoning meetings on the matter saw local city residents protesting the logging company’s use of the commercially zoned lot, and rural and reservation residents speaking out for the new wood hauling endeavor.

Tony and Mary were hopeful for a resolution at the Cortez City Council meeting.

“Starting our operations in COVID, we were told by staff, who are no longer at Cortez, that we could do what we needed to within the Commercial zone of the property we acquired,” said Tony at the public hearing.

The public learned during the meeting that the city had mandated random cessation of operations based on the unfounded allegations by Teri Paul and other members of the trail organization.

Upon later review of the Cortez city land use code, nothing stands out as prohibited – differing vastly in opinion from the city staff. This will also be further detailed in Part Two, as we are going to tell this whole story in hopes that the city will reverse course and allow the vulnerable Nali’ to get their energy for the winter.

But here is a teaser for why the city is so proactive with the trail group’s false complaints, initiating police investigations, and demanding a native small business owner shut down operations based on poorly sourced information. Emails and board membership we reviewed link one city council member to the head of the trails group as well as a shared advisory position within Cortez Parks and Recreation.

This is an uncomfortable coincidence given the unusually effective influence that has delayed or deterred ILC’s “use by right” activity for the entire spring and summer of 2023.

A fine time for public corruption; remember, this decision is preventing Navajo elders from receiving their fuel for the winter.

Dine’ culture recalls a time in 1864 which was similar, at Bosque Redondo. A long march was involved.

Corruption, like the word “firewood,” can be misconstrued. Mistakes can often be made in governance. Protocols in governance – like one department running through the city manager for ‘sanity check’ before acting on another department’s request or recommendation – can help prevent unnecessary mistakes. But when a mistake is discovered, but covered up rather than corrected, there may be a problem of corruption in the bureaucracy.

To be blunt, the interpretation of “commodity” by Nancy and her friends seems to point to either incompetence, corruption, or a bit of both. Initially, the discussion on the term of firewood itself appears to be a mistake by the City Planner, based on the complaints of her city friends.

But since the mistake wasn’t corrected but, rather, resulted in 18 months delays, false allegations, and unfounded complaints, we have a more complex situation.

As stated, we will lay out the connections and sequence of events in part two of this story, but whether we are talking about incompetence or corruption, ILC is losing revenue, the Rez teens remain jobless, and the Navajo elders are bracing for a winter energy crisis.

The site in question is necessary for the firewood hauling operation due to its level nature and its size for turning around vehicles for loading operations. While Tony and Mary own several other parcels, and the City offered a parcel swap, a tour given to local veterans the day after the meeting demonstrated that none of these parcels can meet the unique requirements that led to the initial proposal.

Trucks that can carry 20 cords of wood can easily be loaded at the 1050 Lebanon site with more space available, they can safely enter and exit because of the slower speed limit on Lebanon Road. The sound tests performed by ILC demonstrate that even at increased RPM the noise is drowned out by passing highway traffic or the Cortez Industrial Park with heavy equipment rental less than three hundred yards to the north.

The City Council meeting on September 26, dragged on past 10PM, and ultimately the Mayor and City Council were on the cusp of rejecting the overall zoning of Industrial.

Their imminent decision led Tony and Mary to withdraw their application due to a planned (and apparently retaliatory) 30-day notice of cessation of operation which would have required a mandatory restriction on that commercial property if the industrial zoning request failed.

It’s essentially, “Choose: Your own livelihood or that of the Dine’.”

Astounding and disgusting.

“We should have a powwow sometime, guys. I’m a tribal member,” Tony said to the two native veterans after touring the proposed wood hauling operation.

Tony is a registered Cherokee, and all parties to the proposal are a bit shell shocked that the City of Cortez has decided to insert itself in a mutually beneficial agreement between a native small business owner and the Navajo Chapter Houses.

Incredibly, The Journal article, published for the weekend edition, lauded the decision as an environmental victory over ILC. Apparently, nobody at the local paper cared to investigate, talk to the business owners, or speak to the Chapter Houses. Tony and Mary called The Journal several times throughout the process, but all those calls went unreturned.

A simple investigation by the paper would have easily revealed that the dispute over firewood is based on the incompetence and cultural misunderstanding of white city democrats, and the true victims of this decision are the Nali’ – the Navajo’s grandmothers and generational leadership – on the Rez.

Native and rural readers of The Journal chuckle and call that a ‘Tuesday’ as well. Business as usual in Cortez, it seems.

Delivering the firewood to the Chapter Houses would eliminate the dangerous and burdensome travel for the Navajo communities – hundreds of trips on the fatality-plagued US 160 and US 491.

The 20-cord deliveries that ILC proposed to the Navajo Chapter Houses would equal 40 individual pickup loads, or 15-30 trailer loads depending on the trailer. On narrow, two-lane highways and then over muddy dirt roads for over a hundred miles, with drivers fatigued from splitting and cutting.

The benefits to the Dine’ people from this proposal include reduced highway travel risks, reduced internal Navajo family conflict, hundreds of man hours saved, and energy security for the most vulnerable residents in Cortez and the Rez.

The combat veterans that investigated and contributed to this story have traveled back to split and stack firewood for Nali’ for years – they see it as an obvious and direct impact to our community of older veterans and Navajo elders.

Over twenty Dine’ Chapter Houses are impacted, threatening the well-being of Nali’s this coming winter – all because of false allegations, bureaucratic gridlock, and daytime noise next to an industrial park.

The incompetence of city planners, the first-world problems of the Happy Trails white Karens, and the lack of journalistic curiosity of the local press have led to Cortez’s white democrat leadership celebrating their decision to shove the government into the middle of an agreement between two indigenous parties.

More astonishing, they are celebrating this bureaucratic nightmare as an environmental win – an agreement that reduces waste and reuses commercial byproduct, addresses energy vulnerability in the region, and protects the most vulnerable, indigenous population in the region.

In other words, the white city democrats in Cortez think they know how to protect the environment better than the people who’ve lived on this land long before the founding of this country.

You really can’t make this up.

Thankfully, local residents and business owners in Cortez are beginning to rally behind ILC as the news spreads. The community at large is beginning to look harder into these details – and their current leadership – as many have known Tony’s reputation for decades.

Given the City Council’s decision on Tuesday, it may be too late this season to secure these deliveries. Last winter saw snowfall that was matched only by the 1978 winter, when it started snowing in September, and it didn’t stop until May. If the City Council were to quickly reconsider and approve a short-term compromise for operations, with a guarantee of no further interruptions, Tony could potentially still deliver the wood to the Dine’ – but they must act fast.

As of press time, local sources shared that the city staff is reviewing the decision to allow ILC to provide firewood to the Chapter Houses due to the critical impact on the Navajo. The most distant Dine’ clans and their most vulnerable Navajo population – their elders – may not secure the wood they need for energy this winter if the City refuses to reverse course.

Indigenous People’s Day 2023 – October 9th – is bitterly ironic, it seems, this year. We are certain all the white, democrat City Karens in Cortez will have some sort of celebratory image on their social media next Monday — just under a week after they thwarted a plan that costs them nothing but provides everything to a lonely Nali’ this winter.

With the 2023 SCOTUS decision against the Navajo water rights still fresh in tribal memory, the local coal mine closure a few years ago, and now the proposed delivery of firewood directly to the Navajo Chapter Houses jeopardized, local tribal and rural communities are frustrated.

But while first world problems for white city dwellers can be frustrating, firewood for the Four Corners’ indigenous at-risk population is quite literally a matter of life and death.

Superb article! Most Colorado residents have no knowledge of these types of hardships of people living on the reservations. Thank you for making this problem known.